The Asylum's Beginnings

The history of asylums begins at the turn of the 19th century in England, with the United States quickly following suit. Since then, more asylums began to pop up across the United States and in Canada. In Manitoba, the Provincial and Dominion Governments established the first asylum at Lower Fort Garry in 1871 in connection with the penitentiary.

The asylum operated out of a formerly used Hudson’s Bay Company warehouse. At the time, there was little differentiation between prisoner and patient, so both were housed together. When the Stony Mountain Penitentiary was completed in 1877 everyone was relocated there.

“The poor lunatic did not appeal to the sympathies of the public – a workhouse was good enough for him if harmless, a prison his proper place if dangerous” – T.J. Burgess, 1905.

In 1879 things began to shift. The Federal Government believed that the mentally ill and criminals should be separated. After all, “criminals and lunatics” did not mix. That year an order-in-council passed that all mentally ill cases should be cared for separately from convicts. It comes as no surprise that people were apprehensive of asylums knowing their connection to the penitentiary. However, as the government announced this segregation, families were more compelled to admit their relatives. Numbers of mentally ill patients rose rapidly.

With numbers still rising, it quickly became apparent that something more had to be done. In 1884, the Provincial Government passed an act authorizing the building of an asylum. Around this same time the Dominion Government stated that the mentally ill must be removed from penitentiaries immediately. However, the new hospital at Selkirk was not yet completed so all the patients were transferred from Stony Mountain back to Lower Fort Garry. The hospital in Selkirk was completed in May of 1886 and called the Lunatic Asylum.

Dr. David Young, having cared for the patients at Lower Fort Garry on both occasions became the first Superintendent at the new hospital. The staff hired were the Matron, Euphemia McBride, her assistant Miss Carrie Kennedy, the Chief attendant Mr. George Black, and the Bursar James Colcleugh. Dr. Young was known to be kind and insightful and believed in ethical and humane treatment.

The Buildings

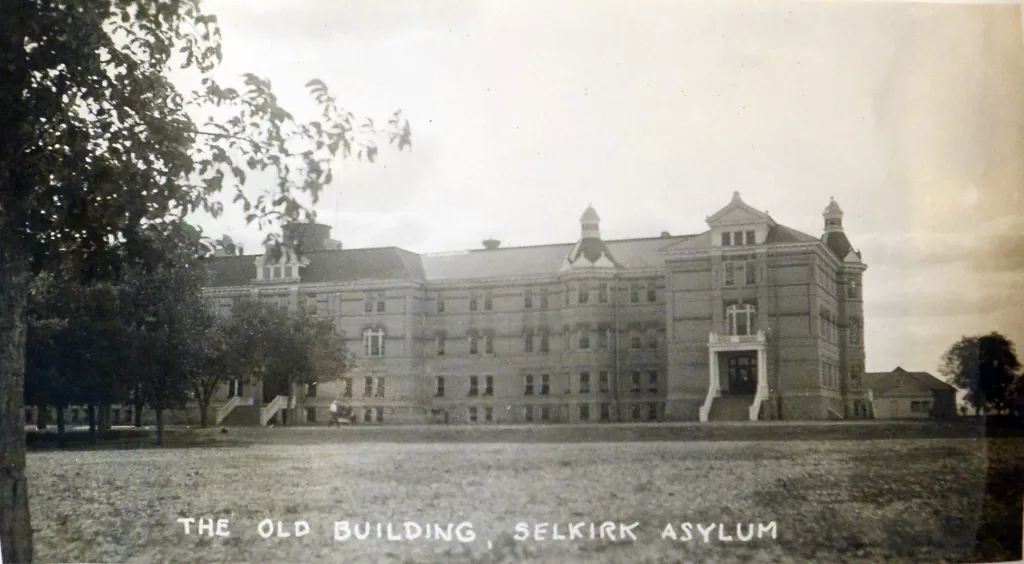

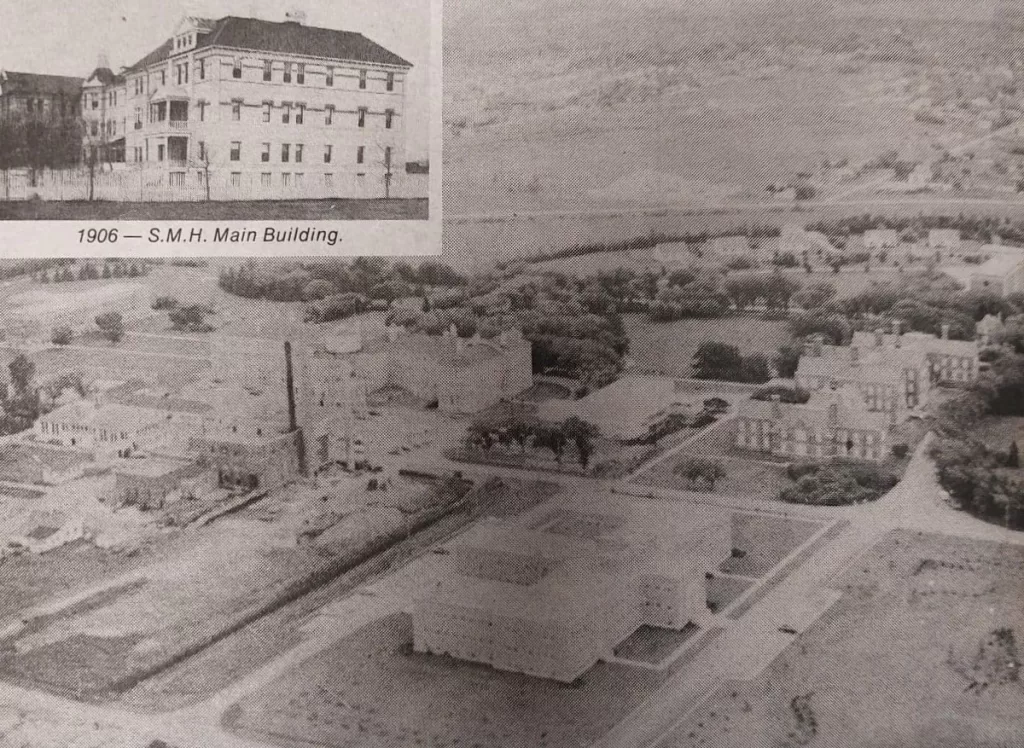

The first building at the Asylum was 100 000 sqft and followed the “shallow H plan” typical of the architectural style for asylums. The floor plan included a central building with wings on either side. The superintendent would be in the center, the men in one wing, and women in the other. The building had a large 12ft wide central corridor, many private rooms, and small wards with a total of 167 beds. There were two small sitting rooms on each floor, a large attic and a basement.

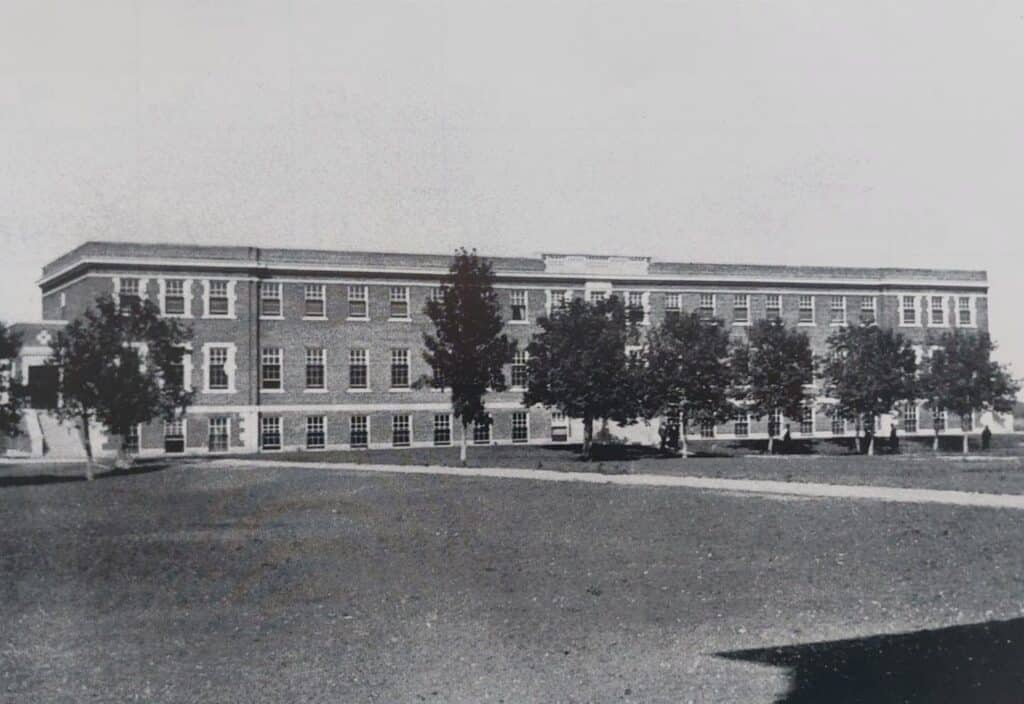

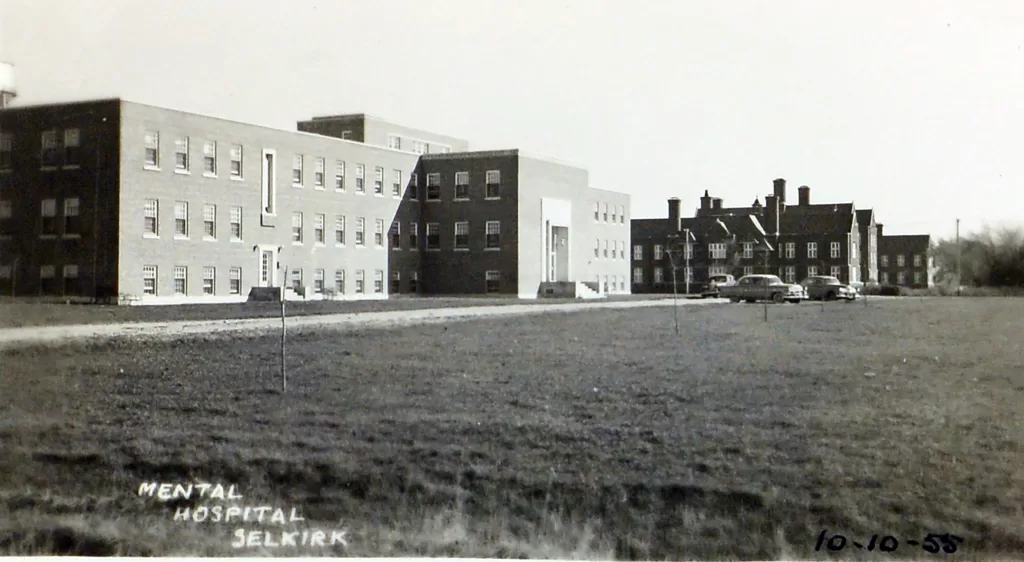

The Reception Unit or Soldiers Pavilion began construction in 1921 and was opened in 1923. This is the present Main Building at the Selkirk Mental Health Centre. The United Kingdom funded its construction in gratitude for Canadian military service during the First World War. The building was subsequently dedicated to the care of veterans. A nurse’s residence was built in 1926 to accommodate the nurses working at the hospital and attending the School of Psychiatric Nursing.

The original Main building was closed and demolished in 1978 due to unsafe living conditions, marking a significant moment in the hospital’s history.

Racist Attitudes

Winnipeg was a popular place for immigrants to settle during the 1800s and 1900s. Selkirk was no different. The conditions which immigrants endured while travelling from Europe to Canada were harsh. Many people experienced sickness, the death of family and friends, isolation, and under-preparedness for Canadian winters. Today it would come as no surprise that someone’s mental health might suffer following these types of events. However, in the early 1900s it was believed that immigrants of certain backgrounds lacked “mental fitness” and were innately predisposed to mental illness. A significant fear developed that “society must be protected from the ravages of mental abnormality.”

“In the past Canada has been careless in the matter of selecting immigrants. In fact, no adequate measures have been adopted to prevent the importation of mental unfits. As a result, probably more than half of our insane and feeble-minded population has come from countries outside of Canada” – C.M. Hincks, 1919.

This fear, coupled with the building of asylums at the end of the 1800s made it easy for those already marginalized to be hidden away from society.

Patient Life

Asylums were designed as self sufficient communities separated from society by farmland and fence line. The asylum had its own land, livestock, stables, and gardens. According to T.J. Burgess in 1898, agricultural work acted as therapy and was the primary method of occupying patient’s time. The men worked outdoors on the farm, and the women worked indoors. Any products produced from the farm were to be sold in Winnipeg in conjunction with the T. Eaton Company.

Separation from the public was not just social, it was physical too. An 8ft fence was built for security purposes and to keep patients “out of sight and out of mind.” Many people were apprehensive of asylums following stories of violent patients. This fear was only affirmed by the physical barrier that a fence presented. The fence was removed 1926 to make the asylum more welcoming. Despite the fence, patients were allowed to come and go during the day, and families were always encouraged to visit.

Crowding

During the first four years after the Manitoba Asylum was built, more patients continued to be admitted from Stony Mountain Penitentiary and from the North West Territories. A few patients were relocated to the Home for Incurables at Portage la Prairie to combat the space issue, and when the Brandon Asylum opened in 1891, some of the strain was alleviated.

However, by the end of the 1800s, the Manitoba Asylum was full, and Dr. David Young had to find new ways of managing the over-crowdedness. He noted in 1904, the need to place patients on cots in the corridors and in the attic. Accommodation consistently failed to keep up with demand.

It is well known that many asylums across Canada provided custodial care at best. This was largely in part to minimal staff and high numbers of patients. Active treatment for patients was often impossible due to such little staff and equipment. Many hospitals including Selkirk, only had one doctor in charge of hundreds of patients at a time. Most hospitals were active during both world wars, which contributed greatly to high patient numbers. High admission numbers resulted in patients sleeping in sitting rooms, dining halls, treatment rooms, hallways, attics, and basements.

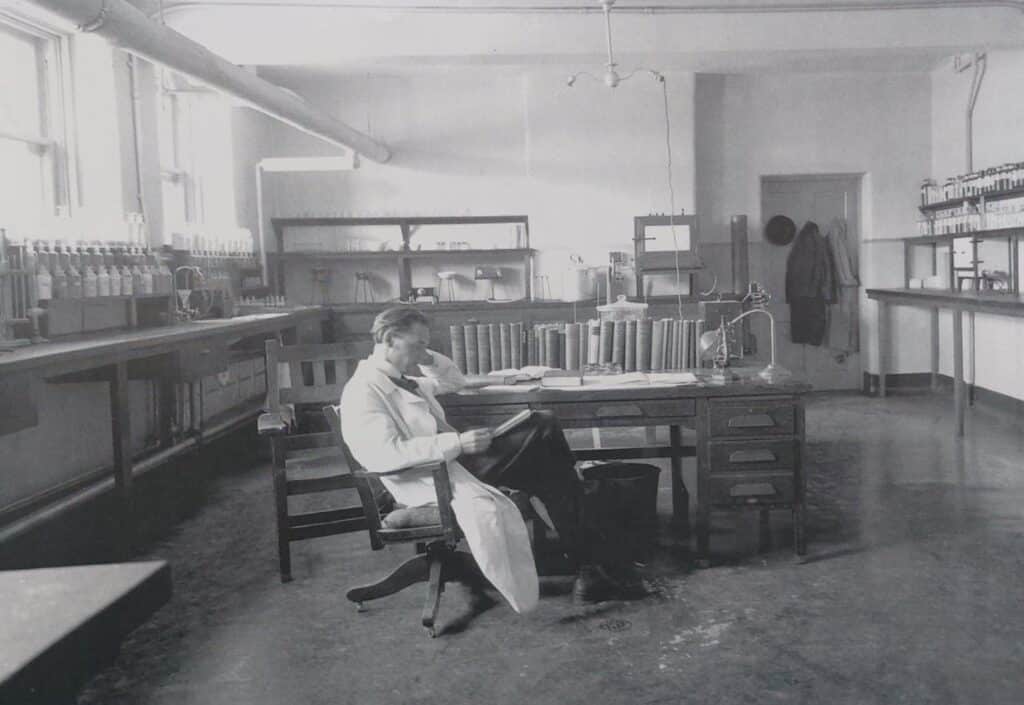

New Medical Treatments

By the 1930s, new research was introduced that insulin shock therapy was successful in treating schizophrenia patients. Insulin shock therapy involved injecting insulin to induce a coma. The patient would be monitored and then given glucose to bring them back to consciousness. This technique was used at the Selkirk hospital in 1936 and was common throughout the 40s and 50s.

The 1940s also brought about the introduction of electro convulsive treatment (ECT) and leucotomies, or more commonly known, lobotomies. By 1954, 258 leucotomies had been performed at Selkirk. ECT is still being utilized in most psychiatric facilities, including at Selkirk. It is now done under anesthetic. It is considered highly effective in the treatment of pervasive depression and some types of schizophrenia, often resulting in complete remission.

During the Second World War it was common for conscientious objectors to be put to work at Mental Hospitals. They were often involved in administering shock therapies. One conscientious objector, Jac. K. Schroeder was vocal about his view of how patients were treated:

“At Schroeder’s first day at Selkirk, he was placed on a ward with 52 patients, 10 of them in straightjackets. The others roamed the plain, undecorated halls. At mealtimes patients would feed the men who were in straight jackets. Schroeder maintains that this practice was ‘… void of understanding, of compassion, of caring and occupational skills. I was appalled to witness such callous treatment of shackled inmates due to a labour shortage.’ ” – Conrad Stoesz, 2011

Changing Times

The 1950s and 1960s brought about changes that reshaped the course of mental health services. New medications were being produced which in some cases offered patients remission from their symptoms to the point where they could return home. Attitudes surrounding mental health also began to change which contributed to the release of patients. This change is evident in 1957 when the patient population at Selkirk hospital began to drop from 1200 to under 280 inpatients.

The Selkirk Mental Health Centre Today

The last asylum in Canada closed in 2009. Since then, many former asylum buildings have been repurposed, or demolished. It is rare that the same buildings are still maintained under changed circumstances, such as at Selkirk.

The hospital not only was one of the largest employers in Selkirk besides the Manitoba Rolling Mills, but it was also instrumental in reducing the stigma of mental health issues. The hospital began as the Manitoba Asylum and experienced many changes throughout its time in operation. By 1973, it had become the Selkirk Mental Health Centre, reflecting these changing attitudes towards mental health.

The Manitoba Asylum Collection

To read more about the Selkirk Mental Health Centre visit the Selkirk Mental Health Centre Archives

Sources

“The Asylum Project in Western Canada,” Arthur Allen – Madness Canada

“Presidential Address – The Insane in Canada,” T.J. Burgess – American Journal of Insanity, 1905

Medicine Manitoba: A Brief History, Ian Carr and Robert E. Bearmish, 1999

“Before the Asylum,” Chris Dooley

“The Mental Hygiene Movement,” Chris Dooley

Managing Madness Weyburn Mental Hospital and the Transformation of Psychiatric Care in Canada, Erika Dyck and Alex Deighton

“From ‘Manitoba Insane Asylum’ to ‘Selkirk Mental Health Centre'” – Selkirk Mental Health Centre Archives

Canadian Journal of Mental Hygiene 1, no. 1, 1919, C.M. Hincks

“History – Selkirk Mental Health Centre” – Province of Manitoba – Mental Health and Community Wellness

“Insulin Shock Treatment in Schizophrenia,” The Canadian Medical Association Journal 41, 1939

“Selkirk Mental Health Centre” – The Eugenics Archives

“‘Are You Prepared to Work in a Mental Hospital?’: Canadian Conscientious Objectors’ Service during the Second World War,” Journal of Mennonite Studies, 2011