Beginnings

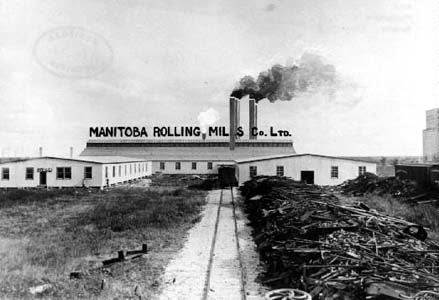

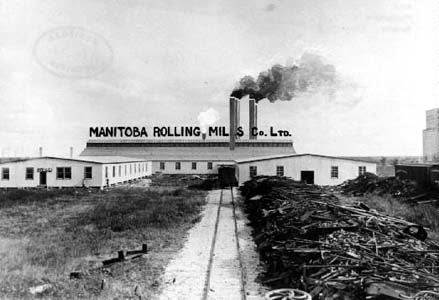

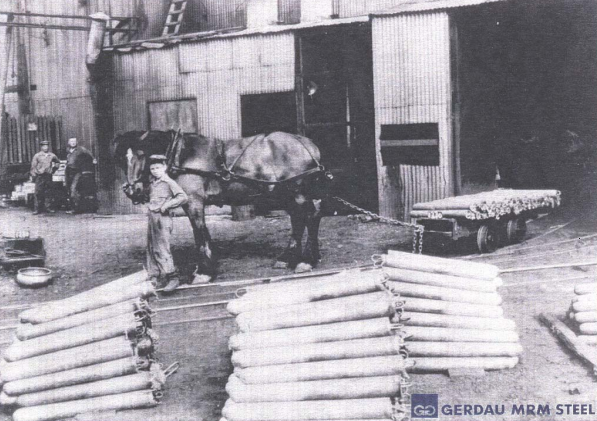

The Manitoba Rolling Mills Company Limited first began in 1907 on Logan Avenue in Winnipeg. Lewis Arthur McElroy, Manufacturer and President of the American Horseshoe Company, and four others invested $10 000 each to get things started.

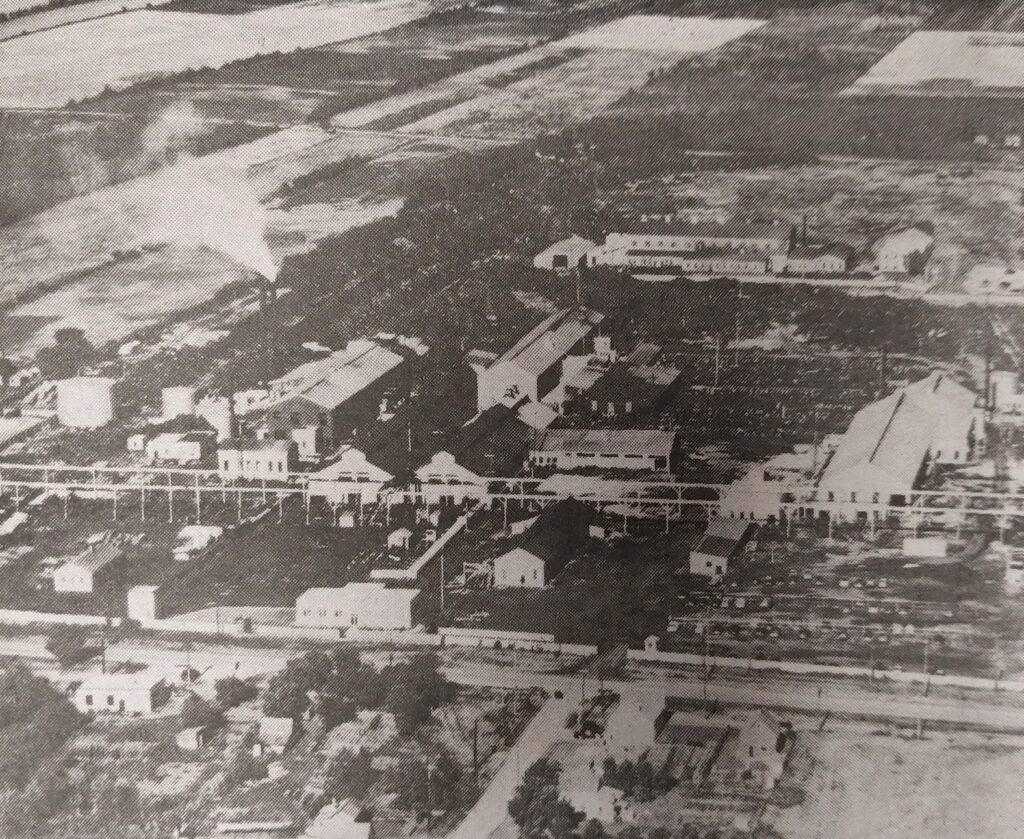

The Mill quickly outgrew its space and in 1909 L.A. McElroy purchased a new site in St. Boniface, tucked in between the CPR and the CNR. At the time the 12 7/10-acre lot cost $15 000. Construction of the new plant took place throughout 1910 and 1911. At this time the Company’s rolling equipment consisted of a 9” and 16” mill, but an additional boiler and furnace were soon added in 1910 to increase production.

Making of a Steel Town

By 1912, the decision was made to sell the property in St. Boniface and transfer the plant to a new location. In Selkirk, several local businessmen saw the benefit the Mill could bring, so they formed the Selkirk Development Company Limited. They purchased 459 acres on the south side of town and negotiations with the Mill began.

The Mill required a fee of $250 000 to cover the cost of relocation, to which the Development Company agreed. As a bonus, they offered the Mill 30 acres for free to start the build.

The deal wasn’t all one sided, however, as the Selkirk Development Company saw this as an investment of a lifetime. They knew that with the relocation and expansion of the Mill, employees would need places to live, and what better place than right next to the Mill, on land now owned by some very clever businessmen?

Both parties agreed to the terms and “the birth of a new industrial era” began. Even Town Council was on their side, approving a bylaw that granted the Company a 40% tax reduction for twelve years. The only condition to this was that the Mill would employ at least 15 local workers.

Construction officially began in the fall of 1913 and continued over the next three years. Over winter, new employees started to arrive but the new houses weren’t built yet. Tradesmen worked long hours attempting to keep up with the demand for shelter. Just in time, the Selkirk Development Company placed its new residential properties on the market and in only four months a quarter of them were sold. Conveniently, the sale of these lots produced the needed funds to meet the $250 000 relocation fee.

Steel to Soldier

The official opening was just around the corner when the news broke that Great Britain had formally declared war on Germany, and Canada was to join the war effort. At that point all the construction workers were laid off, and the Mill was thrown into a period of manpower, material, and business shortages.

In 1917 the Government imposed the War Tax to pay for the costs of the war. This new tax made it harder to fund improvements to the Mill, and there was no return for investors for a while. Negotiations of a possible merger with the Manitoba Bridge & Iron Works Limited arose from the financial challenges. One year later the Manitoba Bridge & Iron Works purchased the company’s capital stock.

Fraud and Embezzlement

Financial hardships at the Mill didn’t stop after WWI ended. In 1920, the unfortunate decision was made to appoint Fred W. Smith as Secretary-Treasurer of the company. Every company that he had worked for in the past had gone bankrupt, however, this connection wouldn’t be made until much later.

F.W. Smith had a fraudulent company named Central Tool Steel & Forgings, which simultaneously had no assets, but had sold hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of scrap to the Mill. F.W. Smith would deposit the cheques, paid out Central Tool Steel & Forgings and withdraw the funds later for his personal use. In doing this he embezzled nearly $200 000 from the Mill over a few years.

At the time the Manitoba Rolling Mills was borrowing a lot of money from the Dominion Bank, and its partner, Manitoba Bridge & Iron Works was in debt by more than $500 000. Had F.W. Smith’s crimes not been discovered the Manitoba Rolling Mills was heading towards bankruptcy. Fortunately, F.W. Smith’s false record books were discovered when he was absent from the office for several days due to appendicitis.

The Dominion Bank was partially liable for the loss caused by F.W. Smith, as the ledger keeper had copies of all the forged signatures, yet still paid out the cheques. Striking a deal, the Dominion Bank adjusted the interest due on the Company’s loans. F.W. Smith was removed from the board and served four years at Stony Mountain Penitentiary.

The Highest High

A few years after F.W. Smith left the Company, production increased, and finances began to equalize. The Mill produced 2000 tons of bar ingots each month, with 400 of those tons being shipped to Japan. After this, international orders from around the globe took off.

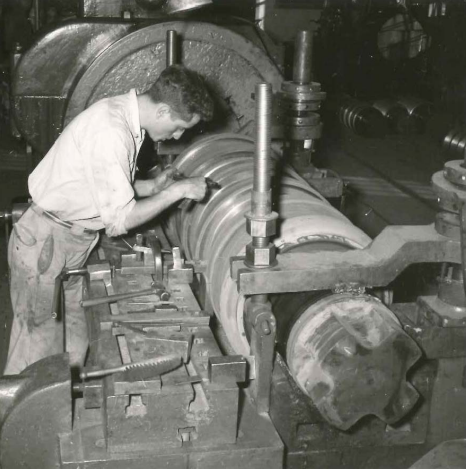

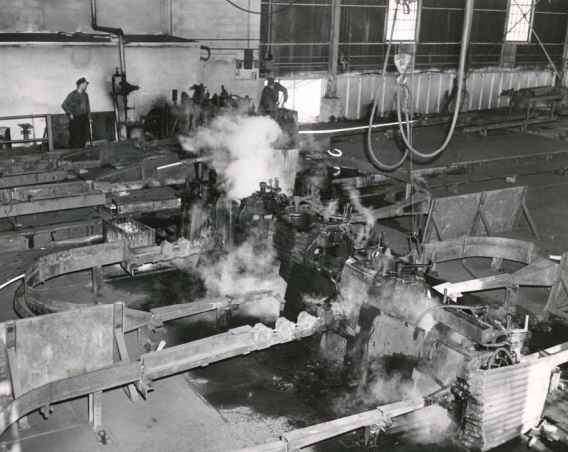

In 1921, Robert Smith was brought from Erie, Pennsylvania to oversee the installation of a new 20-ton open-hearth furnace. The previous coal powered open-hearth furnace required frequent shutdowns and cleaning to maintain its efficiency. This slowed down production, so Robert Smith suggested switching over to oil heating. Under this recommendation the furnace turned out 17 270 tons in 1925 as opposed to the 9000 tons from the old furnace.

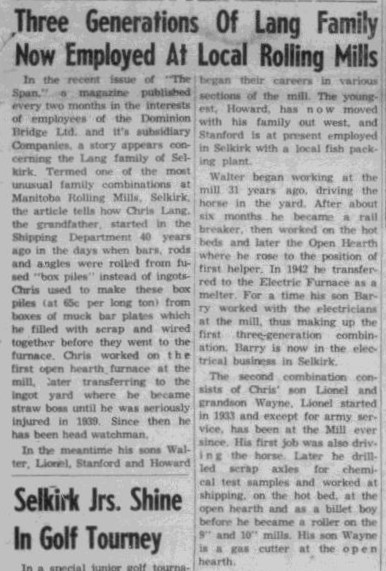

In 1923, General Mill Manager, Peter J. Smith was elected Mayor of Selkirk. The increased national and international demand for products also increased the demand for workers. Available housing in town became a problem yet again, so P.J. Smith recommended Town Council take advantage of the Federal Government’s housing assistance program set in place for returning soldiers. The Mill hired a lot of its previous employees returning from war and boosted the local economy as the country recovered from the war.

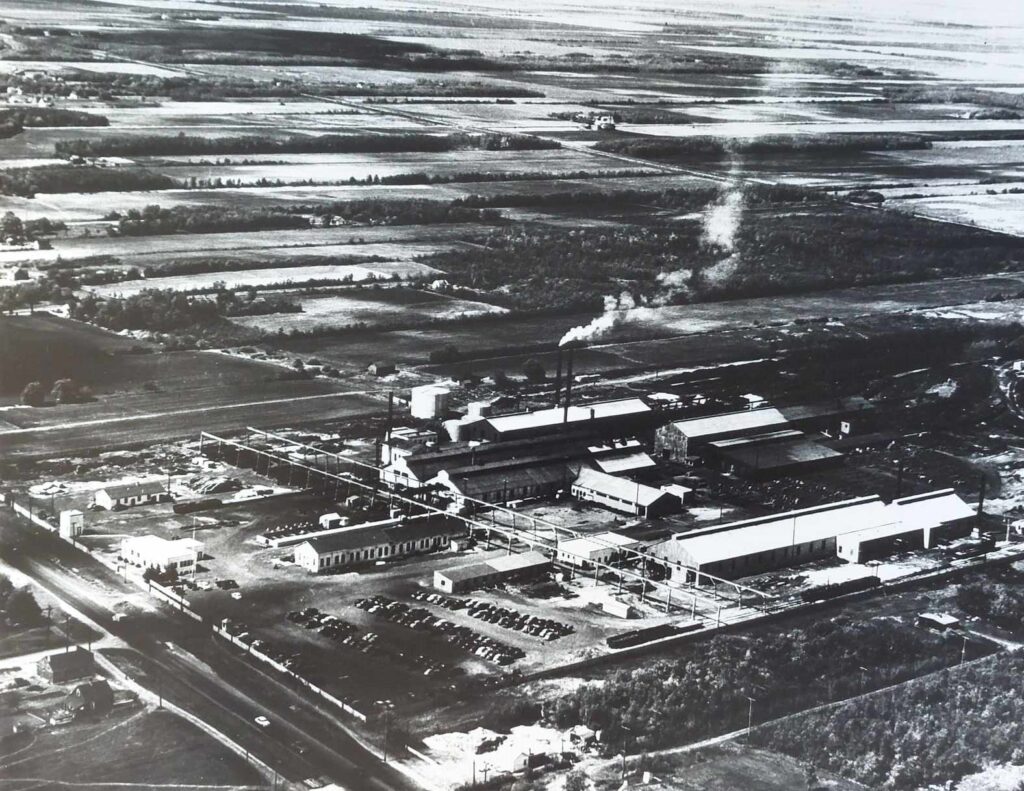

Expansion never ceased throughout the 1920s. In 1928, the Mill purchased an additional second open-hearth furnace that increased the steel making capacity to 160 tons per day. The plant could now operate on a double shift whenever demand rose high enough to require it. The Company also opened a plant in Calgary, Alberta.

In the late 1920s, the Company became a division of the Dominion Bridge Company. The Manitoba Bridge & Iron Works needed a large fabricating shop to handle the larger contracts filtering in. Conveniently, the Dominion Bridge already had a large fabricating plant but lacked a lot of equipment the Manitoba Bridge already had. The merger proved to be an excellent move heading into the financial drought the 1930s would bring.

The Lowest Low

The Depression put an end to the prosperities of the 1920s. By 1932 all work orders had been completed and there was no new business. The Mill shut down for the entirety of the fall and winter. 1933 proved to be the darkest year yet with workers’ hours either reduced or cut entirely. However, Works Manager, Robert Smith never let an employee go hungry or without proper work gear.

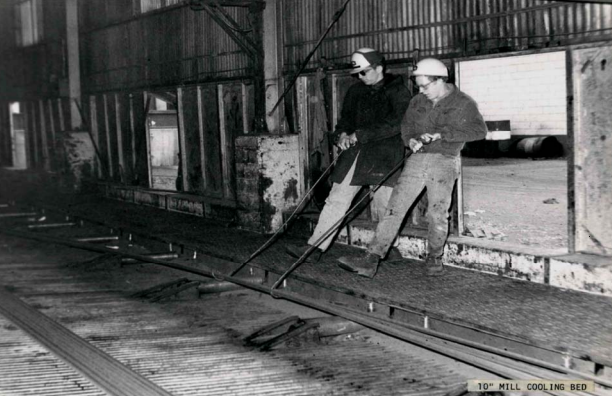

Mill workers were resourceful during these times. The furnaces were hot enough to melt the soles off work boots faster than they could be broken in, so workers would strap old car tires to the bottom of their boots to extend the lifetime of the shoe.

“You could spot a ‘Rolling Mill Man’ by his work clothes and black lunch-pail but especially why his boots, which were soled with auto tires” – Fred Linklater, Selkirk the First Hundred Years, Barry Potyondi.

Manitoba Rolling Mills Collection

Sources

Gerdau Website

Manitoba Business: Manitoba Bridge & Iron Works – Manitoba Historical Society

Selkirk the First Hundred Years, Barry Potyondi

Selkirk’s 75th Anniversary, Elsie MacKay, ed.

Stories of Selkirk’s Pioneers and Their Heritage, Kenneth G. Howard

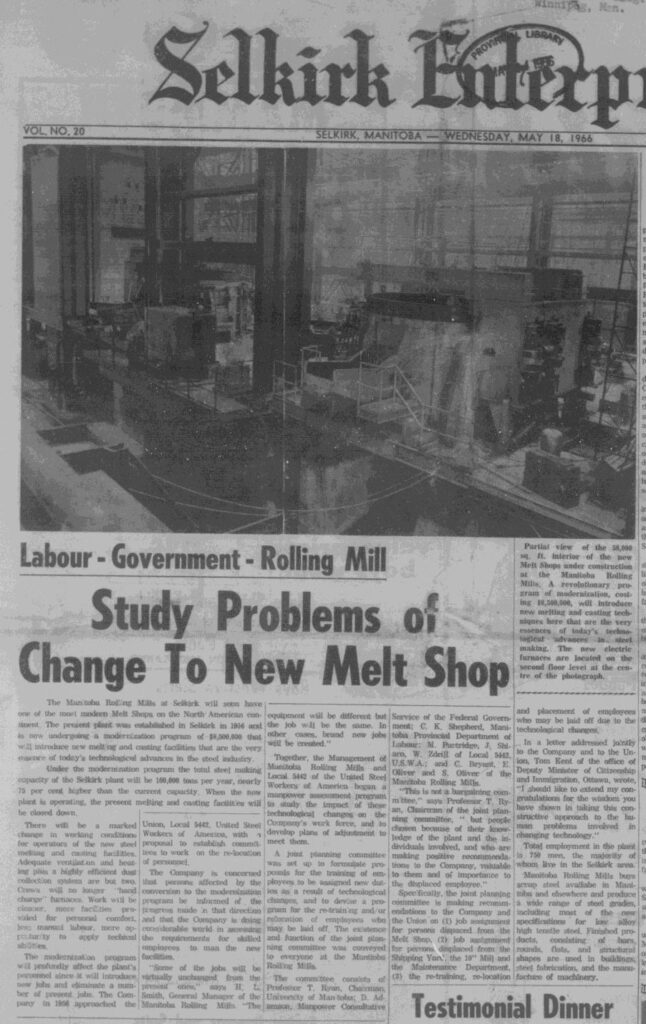

Selkirk Enterprise 1956, 1966, 1971

Selkirk Journal, 1995, 2002

Oral History Interview with Peter Hall

Gerdau History Letter

A Short History of Manitoba Rolling Mill Co. LTD.