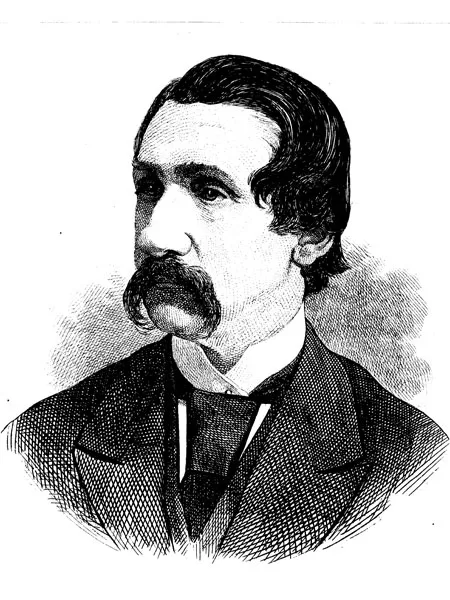

Morris Avenue is named for Manitoba’s second Lieutenant-Governor, Alexander Morris.

Morris was given a street name on the earliest plan of the town. Why? Because Morris changed the development pattern of Selkirk … and all of Western Canada. He paved the way for hundreds of newcomers from Ontario to become wealthy in the west.

However, this wealth came at a cost for many. Morris was responsible for negotiating most of Western Canada’s treaties with Indigenous people.

A Father of Confederation

Morris was a brilliant lawyer who worked in John A Macdonald’s law office. He wrote a book about uniting the British North American colonies to form Canada. It sold 3000 copies – a best-seller. In 1867, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Quebec united. John A. was the Prime Minister and Morris was brought into the cabinet as an advisor.

When Canada took over Manitoba, Morris was appointed its first Chief Magistrate to sort out the legal problems. Legal, social, and economic issues overwhelmed the first Lieutenant-Governor, Adams Archibald who was forced from office in 1872.

Morris, the most experienced federal official in Manitoba, became the province’s next Lieutenant-Governor. His advisers were elected members of the legislature, but he had the power to stop any laws that he (or John A. Macdonald) didn’t agree with. He continued Archibald’s policies of moderation and tolerance between the competing groups in the province.

Unfortunately, Morris’ government passed no laws against land speculation. An influx of newcomers from Ontario led to a free-for-all in the trade of land. The Métis pioneers of Manitoba had been granted river lots – long, narrow strips of land touching the river- by the Hudson’s Bay Company. Under the new Manitoba government, these grants were seen as being invalid.

“Scrip” was issued as a temporary recognition of Métis claims. These “scrip lands” quickly passed into the hands of speculators at very low prices.

Recent studies show that fraud, corruption and even violence played a part in at least two thirds of the Métis land transfers. By 1881, thousands of Manitoba Métis were landless and so packed their belongings into Red River carts and moved west to pioneer the land that would later become Saskatchewan and Alberta.

A River Lot Town

Selkirk’s founders: James Colcleugh, AGB Bannatyne, Sam Bedson, and John Christian Schultz anticipated the transcontinental railway would cross the Red River somewhere between St. Clements Church and (what later became) Selkirk Park. They bought most of the scrip land in the area. River Lots 28-69 became the land on which Selkirk would be built. A group of speculators registered Selkirk’s town plan in 1875.

That first town map drew streets along the edges of the river lots and named the north-south streets after their wives and daughters (eg Annie Bannatyne, Jemima Bedson, Agnes Schultz, Eveline Grieg). Avenues were named after the “celebrities” of the time (Morris, McDermot, Bannatyne, Carnarvon, Cartier). Over time, the other avenues been re-named, but Morris still is recognized for his role in opening the west for settlement.

Selkirk is quite unique in having all of its early streets laid out so as to respect the HBC river lot system of land ownership. Winnipeg and Portage la Prairie also have streets that follow the river lots in certain areas, but Selkirk’s town plan shows the exact river lot boundaries at a glance!

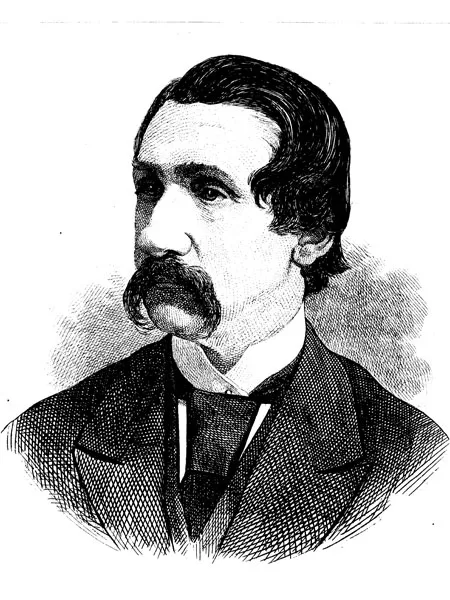

The Treaties

Between 1871 and 1878, First Nations across the west signed treaties with the Canadian government. The chief negotiator was Manitoba and North-West Territories Lieutenant-Governor, Alexander Morris.

The extinction of the buffalo herds and the beginnings of the waves of immigration presented the chiefs of each band with an insolvable problem. How could their people continue with their hunting lifestyle when their main food source – the buffalo – was gone?

In Morris’ book, The Treaties of Canada with the Indians of Manitoba and the North-West Territories he comments that the chiefs, “exhibited great common sense and excellent judgment” (p. 286). He points out that the chiefs are, “harassed with fears as to the future of their children and the hard present of their own lives”. (P.288)

By 1878, famine had gripped on and off-reserve populations. With malnutrition came tuberculosis, diphtheria, smallpox and the deaths of hundreds of children and elders.

Under these conditions, tribes agreed to relinquish claims to their former territories. They agreed to retire to reserved land away from the main settlement areas. They promised to keep the peace as long as the treaties were in place.

The Government of Canada agreed as their part of the treaties to supply the reserves with medicines, farming tools, seed, livestock and instructors to help First Nations begin their lives as agriculturalists.

When the federal government’s supplements were found inadequate, Morris went and re-negotiated Treaties 1 and 2 with more generous terms for the Indigenous. Elsewhere in the West various “Indian agents” interpreted their mandates differently. Several under-spent on agreed-upon supplies. Some, such as P.A.N. Provencher, became wealthy by providing cheap used or broken tools and diseased cattle for reserve use.

This sort of cost-cutting was actively encouraged by both the Mackenzie and Macdonald governments. Morris knew the horrible conditions and desperation facing the Indigenous populations. He recommended generosity by his bosses in Ottawa, but they focused on cutting the cost of the reserves.

Ultimately, Morris was fired because during the smallpox epidemic of 1876-7, he had provided medical assistance and food to the Indigenous population. He “had allowed his conscience, rather than financial concerns, to dictate his actions” (cited P. 105, Clearing the Plains by James Daschuk, U of Regina Press, 2013).

The treaties allowed all later settlement and development in the West to occur.

Indigenous peoples complied with their part of the treaties numbers 1 – 9. From the beginning, the federal government did not! The treaties that were negotiated between respected “partners” were interpreted in Ottawa in the narrowest possible terms. As recent Supreme Court of Canada decisions have shown, Canada’s governments did not live up to the spirit of the treaties.

Federal policies, when examined by modern historians (and Royal Commissions and courts), have revealed the consistent efforts of the Department of Indian Affairs to implement policies of “assimilation and eradication”. (Saul, J.R. The Comeback, 2014, P. 224).

Elements of these policies include the “starvation” strategies of the 1870’s and 80’s, (Tobias, John: “Canada’s Subjugation of the Plains Cree” , in Out of the Background eds. Robin Fisher and Ken Coates, Copp-Clark Pitman Ltd, Toronto, 1988. P 194), the forcing of reserve land surrenders and the use of residential schools.

In 1907, the death rate of residential school students was set by a medical inspector at around “30% in BC” and “50% in Alberta”. His report led to no policy change by the Department of Indian Affairs (King, T, The Inconvenient Indian, 2013. P114). The head of the Department wrote: that such death rates among native children “does not justify a change of the policy …which is geared towards a final solution of our Indian problem.”

The “sixties scoop” (in which children were taken from their parents’ arms to attend residential schools far from their indigenous families, language and culture) and the 1969 White Paper (by which the government sought to strip Indigenous peoples of legal rights) were recent attempts to assimilate native peoples. (King, Thomas, The Inconvenient Indian, p 114).

On October 6, 2017 Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced that compensation in the amount of approximately $800 Million would be given to the survivors and families of the “sixties scoop”. The role of the Welfare, Justice and Penal systems (both provincial and federal) in the demoralization of Indigenous peoples is only now being exposed.

It is the opinion of many journalists, writers and academics that the social chaos affecting Indigenous peoples today is a direct consequence of the conscious programs of the federal government and their provincial allies. What was begun in relative innocence and goodwill by Lieutenant-Governor Morris and the aboriginal chiefs has been perverted by the machinery of governments, past and present.

Morris Avenue Collection

Sources

Clearing the Plains, James Daschuk

Selkirk the First Hundred Years, Barry Potyondi

The Comeback, John Ralston Saul

The Inconvenient Indian, Thomas King